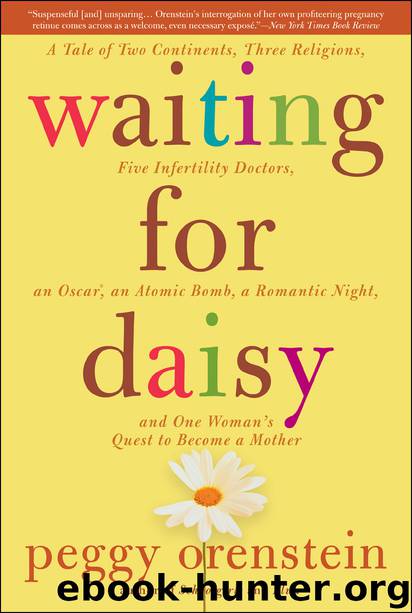

Waiting for Daisy by Peggy Orenstein

Author:Peggy Orenstein

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published: 2010-09-09T04:00:00+00:00

8

JIZO SAVES

I heard the bells before I saw them, following the sound across the courtyard of Zojo-ji, a Buddhist temple in central Tokyo. There they were, lining a shady path: dozens of small figures of infants, each wearing a red crocheted cap and a red cloth bib, each with a bright-colored pinwheel spinning merrily in the breeze. Some had stone vases beside them filled with flowers or smoking sticks of incense. A few were surrounded by juice boxes or candy. A cap had slipped off one tiny head. Before replacing it, I stroked the bald stone skull, which felt surprisingly like a newborns.

The statues were offerings to Jizo, a bodhisattva, or enlightened being, who (among other tasks) watches over miscarried and aborted fetuses as well as dead children. With their hands clasped in prayer, their closed eyes, and serene faces, they are both child and monk, both human and deity. I had seen Jizo shrines many times before. They’re all over Japan, festive and not a little creepy. But this was different. I hadn’t come as a tourist. I was here as a supplicant, my purse filled with toys, to make an offering on behalf of my own lost dream.

Just as I’d feared, my reentry to Tokyo had been bumpy. I kept up with my interviews, had dinner with friends, but my movements felt mechanical, my voice muffled. I tried to convince myself that getting pregnant again at all had been a victory. If I could do it twice, maybe I could do it a third time and it would finally stick. That was, however, an awfully tarnished silver lining to the miasma in my head.

I had never before considered that there was no ritual acknowledging miscarriage in Western culture, no Hallmark card to “celebrate the moment.” There was certainly nothing in traditional Judaism, despite its scrupulous attention to the details of daily life. (My religion was mum on most matters of pregnancy and childbirth until, at least in the Reform and Conservative movements, female rabbis forced a change.) Christianity, too, has largely ignored the subject.

Without form, there is no content. So even in this era of compulsive confession, women don’t speak openly of their losses. It was only now that I’d become one of them, that I’d begun to hear the stories, spoken in confidence, almost whispered. There were so many. My aunt. My grandmother. My sister-in-law. My friends. My editors. Women I’d known for years—sometimes my whole life—who had had this happen, sometimes over and over and over again but felt they couldn’t, or shouldn’t, mention it.

My shock and despair were, in part, a function of improved technology and medical care. In my mother’s era a woman waited until she’d skipped at least two periods before visiting the doctor for a pregnancy test. If she didn’t make it that long, she figured she was simply “late.” It was less tempting, then, to inflate budding suspicions into full-blown fantasies—women often didn’t even tell their husbands the news until the proverbial rabbit had died.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The PCOS Plan by Nadia Brito Pateguana(1086)

Sea of Fertility 1 - Spring Snow by Yukio Mishima(1081)

Anastasia (The Ringing Cedars of Russia Series - Book 1) by Vladimir Megre(1040)

Penis Power by Dudley Seth Danoff(994)

Spring Snow by Mishima Yukio(984)

Healing PCOS by Amy Medling(978)

Life in the Fasting Lane by Jason Fung(953)

Avalanche by Julia Leigh(952)

IVF by Susan Bedford(951)

Taking Charge of Your Fertility : The Definitive Guide to Natural Birth Control, Pregnancy Achievement, and Reproductive Health (9780062409911) by Weschler Toni(947)

Fertile by Emma Cannon(939)

How Change Happens by Duncan Green(910)

Motherhood Reimagined by Sarah Kowalski(884)

The PCOS Diet Plan by Hillary Wright(883)

Fertility Wisdom by Angela C. Wu(867)

Endometriosis by Andrew Horne(866)

Conceivability by Elizabeth Katkin(818)

Fully Fertile by Tami Quinn(800)

Scattered Seeds by Jacqueline Mroz(791)